In 1973, Judy Brewer (then Judy Livers) was married with two young children. A lifelong musician, she worked as a church organist for her large parish. She considered becoming a nurse. A self-described ‚ÄúNavy brat,‚ÄĚ Judy had attended 13 different schools before graduating from high school and was the second oldest among seven siblings.

When her husband was studying for his fire science degree, Judy thought it would be interesting to attend an EMT course. At that time, only those currently working in emergency services, either as paid or volunteer members, were eligible to enroll. Judy had been inspired when reading so she went to a nearby fire department and offered to volunteer.

‚ÄúThe first volunteer station I applied to sent me a letter telling me that the fire service was no place for a woman and told me to go back to my kitchen,‚ÄĚ Judy recalled.

They clearly did not know who they were dealing with.

‚ÄúMy Irish was up,‚ÄĚ Judy said. ‚ÄúI was never in my life told I couldn‚Äôt do something. All I wanted was to be a person that could help others. That letter made me seriously consider a career as a professional firefighter.‚ÄĚ

What Judy did not realize at that time was that there were no women in the career fire service. Women had been volunteers in the fire service and had served on seasonal wildland crews. But no woman had ever been hired as a full-time career firefighter.

That was about to change.

The battle begins

Judy had been accepted as a volunteer with Fairfax County (Virginia) Station 22 when she applied for a full-time position with the Arlington County (Virginia) Fire Department. Her then-husband was initially skeptical (Judy commented that Arlington ‚Äútried to get him to talk me out of it‚ÄĚ) but helped her prepare. He told the department, ‚ÄúJudy‚Äôs going to do what Judy‚Äôs going to do.‚ÄĚ

Arlington County had never had a physical abilities test as part of its hiring process, but when Judy applied, they decided that they needed one ‚Äď but only for her. None of the other applicants was required to take the test, which included tasks like lifting and stacking 100-pound sandbags on a pushcart, moving the cart to another location and unloading it. This was repeated until she had lifted a total of 5,000 pounds. In addition, she also had to lift a hose reel to a shelf 6 feet above her head and hold a 1¬Ĺ-inch straight stream while staying inside a 3-foot square for five minutes, as the pump operator spiked the pressure. All of this was done while wearing outsized gear, including ‚Äúboots that would have been a size 14 on a man.‚ÄĚ

There were also numerous interviews with chief officers. As Judy recalled: ‚ÄúOne of them yelled his questions at me, such as had I ever driven earth-moving equipment. I told him, ‚ÄėNo sir, but I know how to drive a Volkswagen.‚Äô I thought he was asking if I knew how to shift a standard transmission. The guys were spitting as they tried not to laugh. The chief turned red; he was so mad at me.‚ÄĚ

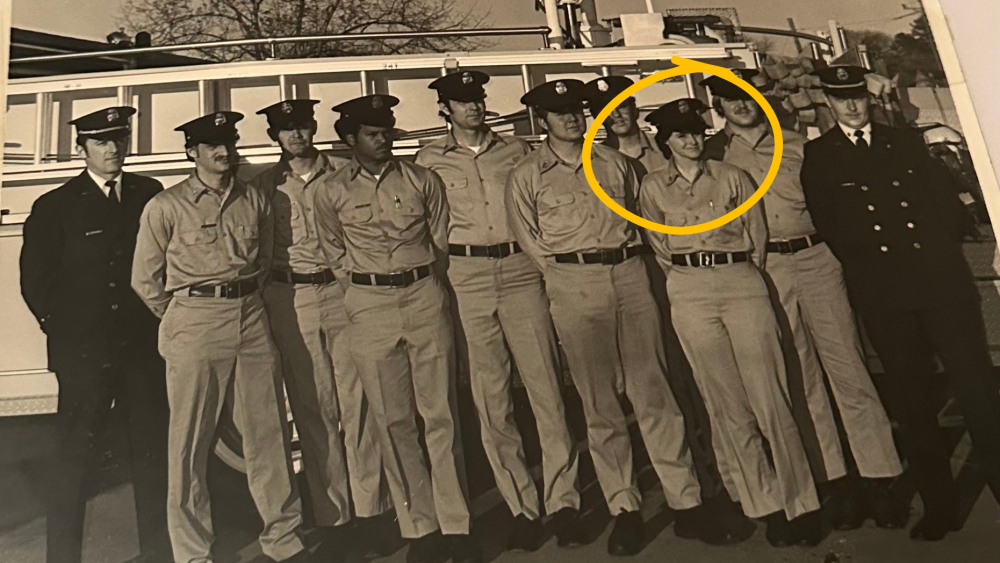

When Judy was hired on March 3, 1974, firefighters‚Äô wives publicly protested. The national media hounded her and her crew relentlessly, with reporters chasing fire apparatus and ‚Äúhanging out of windows trying to get a picture.‚ÄĚ Police were on standby when she did an interview with CBS News, fearing that there could be violence.

Judy was not welcomed by her crew. On more than one occasion, other firefighters tampered with her gear, and then reported her to supervisors for not being prepared to respond. She dealt with this by adopting a routine: ‚ÄúFrom the first day I walked into the firehouse, I spent an hour in the engine room going over every tool, all compartments, all SCBA equipment and anything else I felt I needed to check before I ever entered the fire station.‚ÄĚ

There were no facilities for women in any of the fire stations. She had been told that she could use the battalion chief‚Äôs shower, but that angered her male coworkers, so as a result, ‚ÄúI never took a shower in the station until I was a battalion chief.‚ÄĚ Her locker was in the men‚Äôs restroom, but ‚ÄúI never put anything in that locker, because I wasn‚Äôt supposed to go in the men‚Äôs bathroom.‚ÄĚ (She was, however, required to clean that bathroom.)

It was a lonely life at the beginning. Judy’s husband, who was a firefighter on a different department and who originally opposed her ambition to become a career firefighter, later came to support her. But shiftwork and rotating day and night shifts (Arlington County at that time worked 10/14) along with balancing family life left little time for making friends or finding other avenues of support. The stress of those early days contributed to her divorce in 1978.

A storied career

Things improved at work once Judy made it through the first two years and qualified as a fire generalist, meaning she could then drive all apparatus and operate and maintain all equipment. She also became a paramedic.

In 1984, Judy promoted to lieutenant. By then a few more women had been hired on the department, although Judy was never given the opportunity to work with any of them. In 1985, she promoted to captain and to battalion chief in 1990. In 1996, she was made training division chief.

As an Arlington County firefighter, Judy responded to many difficult and memorable incidents. One that sticks with her to this day was the crash of Air Florida Flight 90 into the 14th Street Bridge and the Potomac River on Jan. 13, 1982. Judy was just getting off shift when the call came in, but she stayed on the ambulance and went to the scene with the crew. Upon arrival, they found 11 people dead on the bridge. ‚ÄúOne guy was beheaded,‚ÄĚ Judy remembered. ‚ÄúThere were a lot of people injured and unconscious.‚ÄĚ Judy acted as triage officer at the event, which ultimately claimed the lives of 74 people aboard the plane and four people on the ground. Only five people who were on the plane survived.

Judy retired in 1999 and moved with her husband John Franklin to Tennessee. She became the director of music at her church and currently sings in the choir. Most recently, she became a certified security officer for her large HOA. She also enjoys sewing and reading.

Doing the right thing

Judy remembers the challenges that came with being the first career firefighter, and she commented wryly, ‚ÄúI sometimes got in trouble for doing the right thing.‚ÄĚ But her fondest memories are ‚Äúthe love of the people who worked so hard as fire personnel and the people we served.‚ÄĚ She added: ‚ÄúI am most proud of touching lives every day and being able to help so many Arlington County visitors and residents. When I walk into a fire station now, I am amazed at the new safety equipment, apparatus, and especially at the relationship today between the men and women who work side-by-side.‚ÄĚ

As for the advice she would give new firefighters today: ‚ÄúYou‚Äôve got to rely on yourself. Listen to people who are trying to teach you. Stay in good physical condition and do something that helps you to relax or clear your mind. Pick and choose your battles. You need to have a good fear of fire, or you shouldn‚Äôt be there. Learn as much as you can, and never take fire for granted.‚ÄĚ

Judy received many letters in the early days, many of them not supportive of her. But one rises in her memory, from a female farmer who wrote to tell Judy how proud she was of her. ‚ÄúI will never forget the encouragement you get from some people that helps you to keep going,‚ÄĚ she said.

Those who came later have never forgotten that someone had to be the first and are grateful that person was Judy Brewer.